by Uche Chukwumerije

IN response to the traditional anniversary inquiries from some newspapers, my progress report on 47 years of Nigeria’s growth is the political message of the fate of Chief Ralph Uwazuruike and other MASSOB leaders incarcerated. The continued detention of Chief Ralph Uwazuruike and some of his comrades is an arrow at the conscience of this nation. A nation destined to endure (as I believe Nigeria is) must invite all its citizens to a level playing ground. They must all be equal players. A nation in which a component is treated as war-vanquished pariah – who must endure a penance of the status of glorified indentured labour for an indefinite time before re-admission into full citizenship – faces the prospects of self-dehydration.

Chief Uwazuruike is a metaphor of the structured castration of Ndigbo ethnic nationality in a Federation founded on and valiantly articulating the ethos of justice and equity. His continued detention is a statement on the glaring inequality and discrimination on which the edifice of the dispensation of democracy, rule of law and equity of access to equity rests. The fate of Chief Ralph Uwazuruike must therefore be seen as an insightful comment on the pace and direction of our evolution towards nationhood in 47 years of existence. It is the intention of this brief plea to examine the political nature of Chief Ralph Uwazuruike’s ordeal, the link between the ordeal and the disposition of his constituent ethnic nationality, the impact of this link on the quality of our democratic dispensation, and the type of verdict which this gives on 47 years of Nigeria’s growth.

The court as arbiter: It is an evident fact that the Nigerian State suspects Chief Ralph Uwazuruike and co as offenders, that they are arraigned before a court of competent jurisdiction, that the independence of the judiciary decrees that the law must take its full course, and that any contrary action may be construed as interference with the process. We respect the hallowed independence of the judiciary, a major pillar of our constitutional democracy.

So far for the legal position. But it is also a political truth that the court is basically an arbitrator in a dispute. It takes two to make a dispute. If one side withdraws from a dispute or modifies his/her stand, the role of the umpire automatically readjusts to the new reality - still in strict compliance with the rules of the game. This case is a dispute between two parties - Uwazuruike and co versus state of Nigeria represented by the Federal Government of Nigeria. The court is the arbiter, weighing the claims of each side. If either side modifies his/her stand, the court has to abide by the new reality.

The political truths: The political character of Uwazuruike’s travails cannot be detached from the legalese of the situation. Let’s briefly understand the political environment. Uwazuruike is of Igbo ethnic stock. An Igbo proverb says that it is only when a madman - who has been vegetating, naked and apparently abandoned, in the village marketplace - comes to harm that the whole village is compelled by the reactions of his family to know that he has relatives.

Uwazuruike’s agitations are basically a cry for equity and justice, a desire which all Igbos share even if many may disagree with him on ways of achieving it. The fate of Uwazuruike is bound to be of concern to Ndigbo. Situated in its Federal context, the political message of Uwazuruike’s fate to Ndigbo acquires a new meaning as a flash of self-discovery. The average Igbo man compares the treatment of Uwazuruike and his MASSOB with the treatment given to his compatriots in other ethnic/regional groups and continues to ask: why are Uwazuruike and Massob treated differently? Ignorant of the legal technicalities of court process, the generality of Igbo people are not able to understand what they see as discriminatory treatment. It is not helpful to blame their perception on ignorance of the law because popular impression is more potent than facts of a given situation in information management.

The question agitating Ndigbo arises from their belief that in objectives, pronouncements and operations, Uwazuruike’s Massob shares similarities with Gani Adams/Faseun’s OPC and Asari-Dokubo’s NDPVF. The leaders of the two other groups have been released, but not Uwazuruike. More on this later. For now, it must be emphasized that in our plural multi-ethnic federation, in which ethnicity stubbornly clings to its prime place as a major vehicle of aggregating interests and the index of corporate identity of groups, ethnic-based youth rebellion has emerged as a symbol of visibility and even virility of an ethnic group. This may be a passing phase in the political evolution of the Federation, if the zoning fad and some elements of our constitution do not unwittingly endow the primordial phenomenon with self-perpetuating strength. For now, ethnic-based power blocs are a reality. For now, youth restiveness represents in a way the arrow head of the continual competition of the silent majorities of ethnic groups for their share of the scarce resources of the federal commonwealth.

All indications point to this link - the sulking silence of the majority of the Yoruba’s over the harsh treatment meted out to OPC leaders, the shock of the Ijaws at the brutal sack of Odi, the resentment of people of Zaki Biam and environs of the military invasion of their communities, and the increasing disquiet of Ndigbo over the discriminatory treatment of Uwazuruike and Massob leaders. Therefore, commonsense suggests that while rule of law follows its sovereign course, the political option of mediation and reconciliation offers a ready expedient short cut to peace.

Negative consequences: In Uwazuruike’s case, failure to pursue this course has produced two negative consequences. The first is the slow but sure alienation of Ndigbo. The generality of Ndigbo are not able to understand the differences in Nigerian state’s responses to what they see as similar offences of three youth organizations, Gani Adams’s OPC, Asari Dokubo’s NDPVF, and Uwazurike’s MASSOB. In similarity, they are militant youth bodies, articulating and championing the causes of their ethnic/regional constituencies - in language always in rhetoric of incitement and overstatement of separatism, in activities often overflowing into youth exuberance, in temperament rarely inclined to democratic accommodation.

But it is the differences in state’s responses to these youth groups that appall Ndigbo. Ndigbo are tuned to the grapevine in times like these. They hear and read that the leaders of these two other youth groups who did carry arms and engaged themselves in violent armed confrontation with the Nigerian state were charged with either illegal possession of arms or treasonable felony, relatively minor offences that carry prison sentences, but that Ralph Uwazuruike and his nine Massob colleagues, who never levied war against the state and who have never been found with arms, were charged with treason, a capital offence, and have consistently been refused bail, on the ground that they have an armory of arms.

Denial of bail

So, for two years the state has been searching everywhere for Massob fictional stockpile of arms. So, for two years, Uwazuruike and his colleagues were denied bail. Ndigbo see this game as another case of a George Bush inventing the fiction of Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and searching for the imaginary dumps in an obvious ploy to hang a bad name on a hated dog. The average Igbo man has therefore come to the conclusion that the Nigerian State is yet to come to terms with the Igbo ethnic nationality, forty years after the civil war and 47 years after independence. They believe that the discriminatory treatment being meted out to Uwazuruike is a deliberate overkill calculated to intimidate and humiliate Ndigbo.

They believe that the continued detention of Uwazuruike is a part of post-civil war attrition which reached its full circle in Obasanjo regime which engineered the final fall of Ndigbo, one of Nigeria’s three major tribes, into a political minority and into the sixth rung of the nation’s power ladder. Ndigbo have never been deceived by the tokenism of Obasanjo’s occasional recognition of individual talents: a dog owner will surely select his most fearless Doberman for the most dangerous thankless jobs.

Ndigbo never saw their future in Obasanjo’s Nigeria - a personification of the post-civil-war dispensation of victors which hit its climax in the emergence of the all conquering President/General who leaves Ndigbo in no doubt that the only Igbo-speaking citizens whom he trusts are the genuflecting subdued subalterns who at the sight of the General would in keeping with the tradition of ancient Rome, instinctively bow their heads in awe and murmur “Te morituri salutamus (We about to die salute you)”

The continued detention of Uwazuruike is a continual reminder to Ndigbo that their position today is one of structured castration. It confirms their worst fears that Obasanjo’s Nigeria has become the permanent parameters of their gilded prison.

Ndigbo’s attitude of mind is a mood which the state cannot afford to foster. The future of Nigeria must erase a situation in which the Nigerian state is alienated against parts of the Nigerian community. The second consequence is the drawback which Uwazuruike’s case inflicts on the development of rule of law. A major catalyst has been injected into the growth of constitutional democracy and rule of law by the Yar’Adua regime’s insistence on strict compliance with rule of law by all, big or small. The continued detention of Massob leaders detracts from the integrity of this revolution in two ways. The first is the continuing spectre of selective justice.

The discriminatory responses of the state to the three youth leaders negate the principle of equality of access of all citizens to equity. The second is the continuing specter of non-compliance with rule of law. Long before his arrest in 2005, the Imo State High Court has given an order specifically restraining SSS from arresting Uwazuruike. The order still subsists.

Yet SSS arrested Uwazuruike and the State has arraigned him in a Court. Rule of law is a major pillar in the bedrock of every enduring democracy. The stunted growth of Nigeria’s 47 years existence attests to this. If the revolution, begun by Yar’Adua on rule of law, takes root, the country will at last find a stable anchor as she confronts the turbulence of delayed maturity.

A superior option: The decline of tension in Niger Delta area and Western states after the release of Asari Dokubo, Gani Adams and Dr. Fasehun clearly demonstrates the superiority of the political option especially in conflicts which have unmistakable political character. The state will reap the same harvest if it releases Chief Uwazuruike and his fellow Massob leaders today. Conversely, the futility of the sledge-hammer approach is amply illustrated by the miserable failure of Obasanjo’s military approach to youth and other social conflicts.

For Ndigbo, the sledge-hammer approach may be provocative and counter-productive. It is like flogging a child a second time to silence his cry after making him in the first instance to start crying with your earlier flogging. An Igbo proverb says that you cannot beat a child and at the same time prevent him from crying. The activities of Uwazuruike, Massob and other Igbo youth bodies are the cries of Igbos for justice and fair play. To silence the youth leaders through sledge hammer devices while the basic causes of the rebellion are not addressed is like beating a child and at the same time preventing the child from crying out.

As Ojo Maduekwe once observed, Ndigbo are one of the few ethnic nationalities who have consistently voted for Nigeria’s national unity with their hands and feet. They live and work and develop everywhere. They are paying their dues for the transformation of the Nigerian state into a federal political community. The discriminatory treatment of Ralph Uwazuruike and Co gives Ndigbo the shock of a child rejected from a home which he considers his own. To thrive, Nigeria has only one way to go - evolve into a political community. A political community must remain an integrated whole. This is the minimum phase of development which a state must attain in order to thrive as a stable nation - an interdependence of autonomous and equal parts operating in a synergy.

Nigeria may be moving in this direction, but she is far from there. She is not yet a political community. She is at best a collection of social classes living in a Hobbesian state or at worst a mixed multitude of victors and vanquished, free men and indentured labour. The continued detention of Uwazuruike provokes a fundamental question. The threat to Nigeria’s future is not Uwazuruike or youth rebellion but the insensitivity of the state to the imperatives of equality and to the varied yearnings of a fledgling political community.

Sunday, September 30, 2007

Sunday, September 23, 2007

Again, The National Question

by Obi Nwakanma

LOOKING at the list of directors and managers of the Nigerian national oil interests, just recently published following the so-called restructuring and redeployments taking place in that sector, one senses the deep meaning of the absence of the Igbo and much of the groups of the old Eastern Nigeria in Nigeria’s formal sector. It is not accidental, we have always said. There are usually symbolic gestures at representing a handful of individuals from the Southern minority ethnic groups, but such symbolic presences do not obscure the fact, that to all intents and purposes, Nigeria’s most strategic national industry is now absolutely under the control of the North.

Individuals who basically, primarily identify as Northerners, now man all the strategic positions in the industry. Now, let me step back a bit, and say, I am personally not distressed by this development, in so far as those individuals manning these sensitive positions earned their places by merit, and are competent managers, and are psychologically and intellectually equipped to play in the very complex and intriguing field of the international oil business and its politics.

Every individual, in other words, deserves his place earned through hard work, dedication, and honesty. I am happy that we have now basically abandoned the debilitating aspects of the quota system, by the look of the profiles of individuals in at least the oil industry, and increasingly in the federal government.

The quota programme no longer holds. That is a fine development. But there is only one troubling aspect of that development: it is that we have not established the grounds to offer a level playing arena for those Nigerians who feel qualified and who may wish to compete for these positions. No vacancies are published; no interviews conducted; no guarantees provided that those who often see themselves as coming now from the wrong side of town can have equal access to the opportunities of the work place and the opportunities of their rights as Nigerians.

This inability makes for some other considerations: it asks us to question the composition of the board of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation and the various sub-corps that make up its vast chain and networks.

Are we to suppose that there are no competent Igbo, Efik, Ibibio, Ogoni, Ijaw, and so on, who may have applied for jobs in the oil industry, and who may have been qualified and deserving of the positions in this industry? So why is the character of the Nigerian National Oil management today unipolar? Let me establish the implications: Although we very often consider oil as a national resource, that question of to whom it really belongs has not been fully settled. There are those who know and who insist that the last civil war was fought over oil.

The upshot is what is now very clear: that the laws that

appropriated those oil fields in 1968, and legally placed it in the hands of the federal government, gave its eternal control to those whoever will control the central government. By various means, the north of Nigeria has placed itself in that position.

The alliance that prosecuted the civil war have had their various turns, and the effect is the devastation of the entire Niger delta, consisting of what was formerly known as the old Eastern and Midwestern region, and the stupendous enrichment of people, mostly from the old Northern and Western region, and a handful of their subaltern allies among the minorities.

The environmental catastrophe that faces the oil producing areas and the increasing poverty of their immediate neighbourhood has instigated the current rebellion in the Niger delta, which is spreading rapidly into a state of lawlessness, as militias, private armies, and mercenary soldiers mutate. I do not think that Nigerians completely comprehend the scenario: although these events are currently taking place, and seem at this moment isolated to the Niger delta, the situation may inexorably spread into an urban warfare, a Somalia like situation, in which once-stable societies implode, and ethnic and sectarian militias, run by war lords, map out territories, and isolate a meaningless government at the center to which none pays allegiance because of its loss of both legitimacy and the capacity to effect national oversight.

That is the emerging scenario which Nigeria’s national security analysts do not seem willing to put in the mix. It would not be impossible for instance, for some one to take over say Surulere, Lagos or Bompai, in Kano or the Fegge area of Onitsha, and establish territorial rights, establish their own laws, collect protection tax, and pay off privateers. This would indeed be, the real meaning of privatization: the privatization of war and of government.

Its stimulant would be, principally the breakdown of families and communities as a result of poverty, displacements, and increasing alienation. It would be stoked by the sense of injustice that comes with a people who feel isolated by the policies of state, and by the lack of opportunities as a result of their presumed location within the meaning of the nation.

At the moment this scenario seems far off: but any close observer of trends within the nation; anybody who has taken note of the pattern of the crime index, and the evolution of values that have shaped the current generation, will notice a fundamental lack of emotion that connects the new Nigerian with the idea of Nigeria. Indeed, from my private studies, while we in the media still put microphones in the mouths of “eminent Nigerians” and “elders,” this young men and women do not care a whit what these guys say, what they represent, or what they care about.

For instance, while a man say like Edwin Clark may go about claiming to be “Ijaw leader” or the plutocrats at Ohaneze ndi Igbo claim to be speaking for “Ndigbo,” the truth is that vast segments of these communities – the younger folk especially - do not feel themselves represented, nor do they care for these individuals; and do not see them as role models; do not respect their views or positions; do not view them as their leaders; they care for only one thing: the opportunity to belong to something that guarantees them livelihood and security, and a different kind of identity.

Many have given up on Nigeria and live here merely as aliens. An Igbo or Efik or Igbira young man or woman who feels segregated and discriminated against, will seek the community of the segregated and discriminated, and establish a common cause and a common front. It would be a matter of time, but they would ultimately challenge their situation.

We are seeing the first signs of that challenge in the rupture of the Niger delta. It is borne primarily from a sense of injustice. But in the appointments that Mr. Yar’Adua has made and approved, reflecting potentially his sense of history as a Northerner, and a potential sense of northern entitlement, he has proved insensitive to the very intricate balances in the federation.

Indeed, the injustice in the structure of the federation, in which Kano State alone receives nearly as much money in federal grants than the entire South-East of Nigeria, is one of those factors that may instigate the incipient rebellion.

The problem is quite stark: the Igbo currently feel isolated, insulted, humiliated, and denied just opportunities as free citizens of Nigeria. At every front: with the use of official population policies, the selection processes, the use of federal control of the national purse string; the use of the force of the state police; the Igbo feel an increasing sense of siege and absence: they are certainly not alone in these feelings: most Nigerians feel that the current state of Nigeria is an impediment to their hopes of a decent life. We should either break it up or make it work. This advice is free.

LOOKING at the list of directors and managers of the Nigerian national oil interests, just recently published following the so-called restructuring and redeployments taking place in that sector, one senses the deep meaning of the absence of the Igbo and much of the groups of the old Eastern Nigeria in Nigeria’s formal sector. It is not accidental, we have always said. There are usually symbolic gestures at representing a handful of individuals from the Southern minority ethnic groups, but such symbolic presences do not obscure the fact, that to all intents and purposes, Nigeria’s most strategic national industry is now absolutely under the control of the North.

Individuals who basically, primarily identify as Northerners, now man all the strategic positions in the industry. Now, let me step back a bit, and say, I am personally not distressed by this development, in so far as those individuals manning these sensitive positions earned their places by merit, and are competent managers, and are psychologically and intellectually equipped to play in the very complex and intriguing field of the international oil business and its politics.

Every individual, in other words, deserves his place earned through hard work, dedication, and honesty. I am happy that we have now basically abandoned the debilitating aspects of the quota system, by the look of the profiles of individuals in at least the oil industry, and increasingly in the federal government.

The quota programme no longer holds. That is a fine development. But there is only one troubling aspect of that development: it is that we have not established the grounds to offer a level playing arena for those Nigerians who feel qualified and who may wish to compete for these positions. No vacancies are published; no interviews conducted; no guarantees provided that those who often see themselves as coming now from the wrong side of town can have equal access to the opportunities of the work place and the opportunities of their rights as Nigerians.

This inability makes for some other considerations: it asks us to question the composition of the board of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation and the various sub-corps that make up its vast chain and networks.

Are we to suppose that there are no competent Igbo, Efik, Ibibio, Ogoni, Ijaw, and so on, who may have applied for jobs in the oil industry, and who may have been qualified and deserving of the positions in this industry? So why is the character of the Nigerian National Oil management today unipolar? Let me establish the implications: Although we very often consider oil as a national resource, that question of to whom it really belongs has not been fully settled. There are those who know and who insist that the last civil war was fought over oil.

The upshot is what is now very clear: that the laws that

appropriated those oil fields in 1968, and legally placed it in the hands of the federal government, gave its eternal control to those whoever will control the central government. By various means, the north of Nigeria has placed itself in that position.

The alliance that prosecuted the civil war have had their various turns, and the effect is the devastation of the entire Niger delta, consisting of what was formerly known as the old Eastern and Midwestern region, and the stupendous enrichment of people, mostly from the old Northern and Western region, and a handful of their subaltern allies among the minorities.

The environmental catastrophe that faces the oil producing areas and the increasing poverty of their immediate neighbourhood has instigated the current rebellion in the Niger delta, which is spreading rapidly into a state of lawlessness, as militias, private armies, and mercenary soldiers mutate. I do not think that Nigerians completely comprehend the scenario: although these events are currently taking place, and seem at this moment isolated to the Niger delta, the situation may inexorably spread into an urban warfare, a Somalia like situation, in which once-stable societies implode, and ethnic and sectarian militias, run by war lords, map out territories, and isolate a meaningless government at the center to which none pays allegiance because of its loss of both legitimacy and the capacity to effect national oversight.

That is the emerging scenario which Nigeria’s national security analysts do not seem willing to put in the mix. It would not be impossible for instance, for some one to take over say Surulere, Lagos or Bompai, in Kano or the Fegge area of Onitsha, and establish territorial rights, establish their own laws, collect protection tax, and pay off privateers. This would indeed be, the real meaning of privatization: the privatization of war and of government.

Its stimulant would be, principally the breakdown of families and communities as a result of poverty, displacements, and increasing alienation. It would be stoked by the sense of injustice that comes with a people who feel isolated by the policies of state, and by the lack of opportunities as a result of their presumed location within the meaning of the nation.

At the moment this scenario seems far off: but any close observer of trends within the nation; anybody who has taken note of the pattern of the crime index, and the evolution of values that have shaped the current generation, will notice a fundamental lack of emotion that connects the new Nigerian with the idea of Nigeria. Indeed, from my private studies, while we in the media still put microphones in the mouths of “eminent Nigerians” and “elders,” this young men and women do not care a whit what these guys say, what they represent, or what they care about.

For instance, while a man say like Edwin Clark may go about claiming to be “Ijaw leader” or the plutocrats at Ohaneze ndi Igbo claim to be speaking for “Ndigbo,” the truth is that vast segments of these communities – the younger folk especially - do not feel themselves represented, nor do they care for these individuals; and do not see them as role models; do not respect their views or positions; do not view them as their leaders; they care for only one thing: the opportunity to belong to something that guarantees them livelihood and security, and a different kind of identity.

Many have given up on Nigeria and live here merely as aliens. An Igbo or Efik or Igbira young man or woman who feels segregated and discriminated against, will seek the community of the segregated and discriminated, and establish a common cause and a common front. It would be a matter of time, but they would ultimately challenge their situation.

We are seeing the first signs of that challenge in the rupture of the Niger delta. It is borne primarily from a sense of injustice. But in the appointments that Mr. Yar’Adua has made and approved, reflecting potentially his sense of history as a Northerner, and a potential sense of northern entitlement, he has proved insensitive to the very intricate balances in the federation.

Indeed, the injustice in the structure of the federation, in which Kano State alone receives nearly as much money in federal grants than the entire South-East of Nigeria, is one of those factors that may instigate the incipient rebellion.

The problem is quite stark: the Igbo currently feel isolated, insulted, humiliated, and denied just opportunities as free citizens of Nigeria. At every front: with the use of official population policies, the selection processes, the use of federal control of the national purse string; the use of the force of the state police; the Igbo feel an increasing sense of siege and absence: they are certainly not alone in these feelings: most Nigerians feel that the current state of Nigeria is an impediment to their hopes of a decent life. We should either break it up or make it work. This advice is free.

Saturday, September 8, 2007

Odenigbo: A church’s celebration of Igbo culture

Anthony ObinnaJoe Nwachukwu, in this piece, examines the relevance of the Owerri Catholic Archdiocese annual Odenigbo lecture series to Igbo culture and chronicles the event’s history.

Odenigbo is an annual celebration initiated and organised by the Catholic Archdiocese of Owerri, Imo State, during which a lecture is delivered in Igbo language by a prominent indigene.

As explained by the Catholic Archbishop of Owerri, His Grace, Most Reverend Dr. Anthony J. V. Obinna, the Odenigbo celebration is aimed at promoting Igbo language, custom and culture with religious connotation.

Precisely on August 27, a week before the commencement of Odenigbo celebration, Archbishop Obinna, while briefing the press, said the 2007 outing would be the 12th celebration of the Owerri Archdiocesan Odenigbo Day, which started in September 1996. The event, he explained, had attracted citizens of Igboland beyond Africa. He added that it had been enriched by “the spiritual grace of good news, lovely aspects of the Igbo culture and challenging lectures of Igbo scholars who speak on various important topics in the Igbo language.”

According to him, through the Owerri Archdiocesan Odenigbo celebration, the church recalled the elevation of the diocese to the apex church position of Archdiocese in Igboland and renewed its commitment to proclaiming the good news of salvation to Ndigbo, the entire land and humanity at large. This, according to the archbishop, had entailed the glorification of God and the rededication of Ndigbo to the one true God through the Lord Jesus Christ in worship and thanksgiving.

He stated that it had involved the promotion of authentic human and Igbo values, including the Igbo language, through recreation, entertainment and life reformation lectures.

“The aim of the Owerri Archdiocesan Odenigbo celebration is to glorify God for all His gifts to humanity, to rejoice in our restored dignity as fellow humans in Christ and in ‘Igboness,’ to refresh and refine our spirits and bodies with elevating entertainment and direct our minds, hearts and fellowship towards ennobling aspirations and actions.

“This year, a distinguished daughter of Igboland, the Director-General of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), Professor Dora Akunyili, is the active human and cultural ingredient helping to attract Umu Igbo and others to the celebration. “She will speak on a topic very relevant to the health and integrity of humans, particularly Ndigbo, namely Effective Drugs: the Genuine Art and Science and Its Fake,” he said.

Answering reporters’ questions, Archbishop Obinna said this celebration had already acquired a respect place in the heart of Ndigbo at home and abroad, adding that while helping to purify and dignify Ndigbo locally, it had helped to honour them nationally and internationally.

“It has stimulated interest on the internet. It is not a money making venture, it is a human development and enhancement project. Nevertheless, it requires financial support to sustain it into the future. I appeal to the Igbo public and lovers of goodness to show their solidarity in this regard,” he said. The first day of the Archdiocesan Odenigbo celebration usually involves a variety of cultural entertainment which includes dances of Igbo culture, wrestling contests and drama.

The second day begins with a thanksgiving Holy Mass. This is followed by fund raising activities for the projects of the Archdiocese. Some light refreshment is then offered for the relaxation of the people and to prepare the audience for the final stage of the Odenigbo lecture.

The first celebration of Owerri Archdiocesan day took place on September 6 and 7, I996. The topic of the maiden lecture in the Odenigbo series was Olumefula-Asusu Igbo na Ndu Ndigbo and it was delivered by Professor Emmanuel Nolue Emenajo, the Director National Institute for Nigerian Languages, Aba, Abia State.

The second Archdiocesan day celebration was held between September 5 and 6, 1997. The Odenigbo lecture for that year had as its theme: Chibundu-Ofufe Chukwun’s Etit Nd’Igbo. The lecturer was Reverend Father (Dr.) Theophilus Ibegbulem Okere of Catholic Archdiocese of Owerri. The topic of the lecture in 1998 was Onyegbule-Ndigbo na Nsopuru Ndu. The lecturer was the late Reverend Father (Professor) Edmund Emefie Ikenga-Metuh, who happened to be a victim of the Kenyan plane crash at Ivory Coast in 2000.

Reverend Father Metuh was a priest of the Catholic Archdiocese of Onitsha in Anambra State and a professor of African Religion. He was a lecturer at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State.

In 1999, the Odengibo lecture took place on August 17. The topic was Echi di Ime: taa Bu Gboo. It was delivered by a most illustrious son of the land, the internationally celebrated novelist, Professor Chinua Achebe. The lecture generated so much controversies ranging from political to social and religious viewpoints at both local and international levels.

The topic for the Odenigbo lecture in 2000 was Ujunwa: Anuri uwa Niile. The lecture was delivered by the founder of the Odenigbo lecture series, Most Reverend (Dr.) Anthony John Valentine Obinna, the Catholic Archbishop of Owerri. The 2001 lecture topic was Uwa Ohuu Akamgbachere Igbo. The lecturer was Professor John Egbulefua of the Pontifical Urban University, Rome, Italy.

In 2002, the Odenigbo lecture’s topic was Agbwa Bu mma Nzuzi Na Nzujo Unnuigbo to which justice was done by a seasoned Igbo daughter and scholar, Dr. (Mrs.) Gabriella Ihuarugo Nwaozuzu. The 2003 Archdiocesan day celebration was held between September 12 and 13. The topic of the lecture was Odozi Obodo Ochichi Maka Ezi Oganihu Ala Igbo, a lecture delivered by a renowned professor and priest at the Urban University, Rome, Reverend Father (Dr.) Godfrey Onah.

The topic of the lecture in 2004 was Ahuike Ike Ogwu Na Ike Ekpere. It was delivered by Dr. Barnabas Anelechi Chukwuezi, a seasoned medical practitioner. In 2005, the lecture’s topic was Akobundu: Amamihe Na Ebute Oganihu. It was delivered by Dr. Victor Irokanulo Okereke, an associate professor of Environmental Science and Engineering at the University of New York, Morishivile, United States.

The 2006 Archdiocesan day celebration was held between September 2 and 3. The topic was Ijeoma Ofo Ndigbo Na-Ago. The lecture was delivered by the Provincial Co-ordinator of the Justice Development and Peace Commission (JDPC), Owerri Province, Reverend Father (Dr.) Maduakolam I. Osuagwu.

This year’s Archdiocesan Day celebration was held on August 31 and September 1. The topic for the Odenigbo lecture was Ogwu dire Ezi Nka Nruruaka and as Most Reverend Obinna had said, it was delivered by Professor Akunyili.

Anthony ObinnaJoe Nwachukwu, in this piece, examines the relevance of the Owerri Catholic Archdiocese annual Odenigbo lecture series to Igbo culture and chronicles the event’s history.

Odenigbo is an annual celebration initiated and organised by the Catholic Archdiocese of Owerri, Imo State, during which a lecture is delivered in Igbo language by a prominent indigene.

As explained by the Catholic Archbishop of Owerri, His Grace, Most Reverend Dr. Anthony J. V. Obinna, the Odenigbo celebration is aimed at promoting Igbo language, custom and culture with religious connotation.

Precisely on August 27, a week before the commencement of Odenigbo celebration, Archbishop Obinna, while briefing the press, said the 2007 outing would be the 12th celebration of the Owerri Archdiocesan Odenigbo Day, which started in September 1996. The event, he explained, had attracted citizens of Igboland beyond Africa. He added that it had been enriched by “the spiritual grace of good news, lovely aspects of the Igbo culture and challenging lectures of Igbo scholars who speak on various important topics in the Igbo language.”

According to him, through the Owerri Archdiocesan Odenigbo celebration, the church recalled the elevation of the diocese to the apex church position of Archdiocese in Igboland and renewed its commitment to proclaiming the good news of salvation to Ndigbo, the entire land and humanity at large. This, according to the archbishop, had entailed the glorification of God and the rededication of Ndigbo to the one true God through the Lord Jesus Christ in worship and thanksgiving.

He stated that it had involved the promotion of authentic human and Igbo values, including the Igbo language, through recreation, entertainment and life reformation lectures.

“The aim of the Owerri Archdiocesan Odenigbo celebration is to glorify God for all His gifts to humanity, to rejoice in our restored dignity as fellow humans in Christ and in ‘Igboness,’ to refresh and refine our spirits and bodies with elevating entertainment and direct our minds, hearts and fellowship towards ennobling aspirations and actions.

“This year, a distinguished daughter of Igboland, the Director-General of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), Professor Dora Akunyili, is the active human and cultural ingredient helping to attract Umu Igbo and others to the celebration. “She will speak on a topic very relevant to the health and integrity of humans, particularly Ndigbo, namely Effective Drugs: the Genuine Art and Science and Its Fake,” he said.

Answering reporters’ questions, Archbishop Obinna said this celebration had already acquired a respect place in the heart of Ndigbo at home and abroad, adding that while helping to purify and dignify Ndigbo locally, it had helped to honour them nationally and internationally.

“It has stimulated interest on the internet. It is not a money making venture, it is a human development and enhancement project. Nevertheless, it requires financial support to sustain it into the future. I appeal to the Igbo public and lovers of goodness to show their solidarity in this regard,” he said. The first day of the Archdiocesan Odenigbo celebration usually involves a variety of cultural entertainment which includes dances of Igbo culture, wrestling contests and drama.

The second day begins with a thanksgiving Holy Mass. This is followed by fund raising activities for the projects of the Archdiocese. Some light refreshment is then offered for the relaxation of the people and to prepare the audience for the final stage of the Odenigbo lecture.

The first celebration of Owerri Archdiocesan day took place on September 6 and 7, I996. The topic of the maiden lecture in the Odenigbo series was Olumefula-Asusu Igbo na Ndu Ndigbo and it was delivered by Professor Emmanuel Nolue Emenajo, the Director National Institute for Nigerian Languages, Aba, Abia State.

The second Archdiocesan day celebration was held between September 5 and 6, 1997. The Odenigbo lecture for that year had as its theme: Chibundu-Ofufe Chukwun’s Etit Nd’Igbo. The lecturer was Reverend Father (Dr.) Theophilus Ibegbulem Okere of Catholic Archdiocese of Owerri. The topic of the lecture in 1998 was Onyegbule-Ndigbo na Nsopuru Ndu. The lecturer was the late Reverend Father (Professor) Edmund Emefie Ikenga-Metuh, who happened to be a victim of the Kenyan plane crash at Ivory Coast in 2000.

Reverend Father Metuh was a priest of the Catholic Archdiocese of Onitsha in Anambra State and a professor of African Religion. He was a lecturer at the Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State.

In 1999, the Odengibo lecture took place on August 17. The topic was Echi di Ime: taa Bu Gboo. It was delivered by a most illustrious son of the land, the internationally celebrated novelist, Professor Chinua Achebe. The lecture generated so much controversies ranging from political to social and religious viewpoints at both local and international levels.

The topic for the Odenigbo lecture in 2000 was Ujunwa: Anuri uwa Niile. The lecture was delivered by the founder of the Odenigbo lecture series, Most Reverend (Dr.) Anthony John Valentine Obinna, the Catholic Archbishop of Owerri. The 2001 lecture topic was Uwa Ohuu Akamgbachere Igbo. The lecturer was Professor John Egbulefua of the Pontifical Urban University, Rome, Italy.

In 2002, the Odenigbo lecture’s topic was Agbwa Bu mma Nzuzi Na Nzujo Unnuigbo to which justice was done by a seasoned Igbo daughter and scholar, Dr. (Mrs.) Gabriella Ihuarugo Nwaozuzu. The 2003 Archdiocesan day celebration was held between September 12 and 13. The topic of the lecture was Odozi Obodo Ochichi Maka Ezi Oganihu Ala Igbo, a lecture delivered by a renowned professor and priest at the Urban University, Rome, Reverend Father (Dr.) Godfrey Onah.

The topic of the lecture in 2004 was Ahuike Ike Ogwu Na Ike Ekpere. It was delivered by Dr. Barnabas Anelechi Chukwuezi, a seasoned medical practitioner. In 2005, the lecture’s topic was Akobundu: Amamihe Na Ebute Oganihu. It was delivered by Dr. Victor Irokanulo Okereke, an associate professor of Environmental Science and Engineering at the University of New York, Morishivile, United States.

The 2006 Archdiocesan day celebration was held between September 2 and 3. The topic was Ijeoma Ofo Ndigbo Na-Ago. The lecture was delivered by the Provincial Co-ordinator of the Justice Development and Peace Commission (JDPC), Owerri Province, Reverend Father (Dr.) Maduakolam I. Osuagwu.

This year’s Archdiocesan Day celebration was held on August 31 and September 1. The topic for the Odenigbo lecture was Ogwu dire Ezi Nka Nruruaka and as Most Reverend Obinna had said, it was delivered by Professor Akunyili.

Sunday, September 2, 2007

Ikejiani: Remembering his tribute to Zik II

by P. Chudi Uwazuruike

Continued from last week

He comforted me and replaced the counterfeit money. He proceeded to make all the arrangements for all of us. True enough, came December 1938, the eight of us left Apapa and sailed for the United States of America to embark on further studies. It was a very historic event in Nigeria with throngs of people coming to see us off at the wharf.

Zik assisted dozens of Africans to go on to the United States for university education. In assisting and helping us and those that had gone before us, like late Kwame Nkrumah just about a year after he has returned to Nigeria from Ghana was a great way of showing the light. K.O. Mbadiwe, A.A. Nwafor Orizu, and others like Jones-Quartey, Karimu Disu, Kalu Ezera, etc., all travelled under his aegis.

I met Zik again in August 1948 when I returned from the United States of America and Canada , after many years of sojourn there. It happened that my wife was a white lady, nee Marjorie Carter. Rumour had reached the Igbo State Union that I was returning with wife. The Igbo Union executives met with Zik and informed him about what they had heard. They said that because of that, they would not give me the reception they were planning for me. He asked them whether I wrote to them that I was returning and they should accord me a reception. They said no. He thereupon told that he did not think that I would be expecting their reception. Zik added that he was going to Apapa to meet me and my wife and that we were going to be his host as long as we stayed in Lagos . That shocked them and completely cured them of the race hatred which they harboured. That notwithstanding, I was given receptions galore on our return wherever we went throughout Igboland.

From the moment of my return in 1948, a deep and abiding friendship developed between Zik and I. This friendship grew by leaps and bounds over the years - and I came to learn a lot about him. From that incident in 1948, I realized that this man called Zik was not prejudiced against white people. As an Igbo, like him, raised in the same environment that influenced his basic character, I communicated with him in the same language and understood the riddles and real meanings behind his remarks, statements and messages. Our friendship throughout the years until his death, was based on mutual trust and respect. As one brought up in the tradition of Igbo custom, Zik was my elder in age and indeed in everything else. Igbo society believes that although no condition is permanent, still no human society can achieve absolute equality for its citizens as there are distinctions of age, sex and wealth. Yet the dignity of every man was absolute. For instance, I am self-assertive as an Igbo, and Zik respected and valued it; as an Igbo also, I am not subservient, nor do I pay unquestionable obedience to everything Zik said. Zik admired and respected that also.

Zik had great faith in the immense ability of the peasantry to understand, and believed that they were just waiting to be enlightened. ..The editorials in the newspapers, especially those of the West African Pilot, were complemented by the humour, intelligence and acerbic satires of the various columnists. Among the best known columns were "Inside Stuff," written by Zik himself; "As I see it" by O.A Alakija; "A New Education for a New Africa" by Professor Eyo Ita; among others. The writers were all nationalists, and their essays were not only nationalistic but also educational. They showed black Africans and Nigerians the light. Many became prodigious readers, enabling them to acquire the dramatic force of conviction that propelled them to dare. Those columns became a form of literature for every school boy and girl, every worker, every one who could read and write. Certainly there began in Nigeria and all black Africa , a period of enlightenment, and the flowering of a new set of ideas about colonial rule and freedom from it.

As an instrument of propagating nationalism, equality of mankind and self-pride, their anti-colonial and nationalistic effect on the generation, our generation, and the era between 1937 and 1960 was unparalleled. No other previous or contemporary anti-colonial newspaper in Nigeria or elsewhere in black Africa had produced anything comparable in their influence towards a national spirit and towards Nigerian oneness.

In attacking imperialism and educating Nigerians, Zik’s writings were designed to appeal to every class - the common people, the youth, the intellectual, the rural as well as the city workers, and in a language which suited their emotion and which they understood. … He was a marvelous mob orator especially when he spoke concerned with the genuine hatred of imperialism and racial discrimination. His speeches always overwhelmed his audience, always moved them to immense enthusiasm, to a magnificent understanding of the evils of imperialism…

It is true that Zik’s age also had other politicians who emerged to join with him in the fight for independence, men no less sincere and probably no less devoted. But no one so vigorously, so single handedly or so successfully tried, as he did, in making every word and every act of his life a means towards a single objective, freedom from Britain as a SINGLE UNIFIED NIGERIAN NATION. As James Coleman testified, "During the fifteen year period (1939-1945) Nnamdi Azikiwe was undoubtedly the most celebrated nationalist leader on the West Coast of Africa, if not, in all tropical Africa", and that he was "the most single precipitator of the Nigerian awakening."

Certainly in 1930s and 1950s, Zik was the sole national leader, the sole nationalist inspirer, the sole intellectual, moral and political dictator in Nigeria against imperialism. He created an irresistible nationalist movement willing to overthrow colonial rule by peaceful means. He was an indomitable Moses preparing to lead his people out of Egypt . And he did. The emergence of Zik and his newspapers gave a new eloquence and ardor, a richer, more meaningful and emotionally charged anti-colonial message which profoundly effected more black Africans and Nigerians than ever before. No other black African or Nigerian before him or after, could claim to have aroused so many people across all the tribes, with direct and powerful nationalist political influence, as he did. Certainly, he exercised an intellectual and nationalist influence over many black Africans and Nigerians the strength of which was unique. He was the child of Africa and Nigeria and of Africa and Nigeria ‘s twentieth century prophetically calling for the end of colonialism and without violence. The verdict of history will record that this man Zik, had he done nothing else, that alone would have been sufficient to have assured him a lasting fame.

In conclusion, what Ikejiani said in closing the Foreword in the tribute to his friend, could very well he said of him by many who came to know him closely: He was indeed a great man. His life all reminds us about Longfellow’s Psalm of Life: Lives of great men all remind us; We can make our lives sublime, and in departing leave behind us foot prints in the sands of time."

by P. Chudi Uwazuruike

Continued from last week

He comforted me and replaced the counterfeit money. He proceeded to make all the arrangements for all of us. True enough, came December 1938, the eight of us left Apapa and sailed for the United States of America to embark on further studies. It was a very historic event in Nigeria with throngs of people coming to see us off at the wharf.

Zik assisted dozens of Africans to go on to the United States for university education. In assisting and helping us and those that had gone before us, like late Kwame Nkrumah just about a year after he has returned to Nigeria from Ghana was a great way of showing the light. K.O. Mbadiwe, A.A. Nwafor Orizu, and others like Jones-Quartey, Karimu Disu, Kalu Ezera, etc., all travelled under his aegis.

I met Zik again in August 1948 when I returned from the United States of America and Canada , after many years of sojourn there. It happened that my wife was a white lady, nee Marjorie Carter. Rumour had reached the Igbo State Union that I was returning with wife. The Igbo Union executives met with Zik and informed him about what they had heard. They said that because of that, they would not give me the reception they were planning for me. He asked them whether I wrote to them that I was returning and they should accord me a reception. They said no. He thereupon told that he did not think that I would be expecting their reception. Zik added that he was going to Apapa to meet me and my wife and that we were going to be his host as long as we stayed in Lagos . That shocked them and completely cured them of the race hatred which they harboured. That notwithstanding, I was given receptions galore on our return wherever we went throughout Igboland.

From the moment of my return in 1948, a deep and abiding friendship developed between Zik and I. This friendship grew by leaps and bounds over the years - and I came to learn a lot about him. From that incident in 1948, I realized that this man called Zik was not prejudiced against white people. As an Igbo, like him, raised in the same environment that influenced his basic character, I communicated with him in the same language and understood the riddles and real meanings behind his remarks, statements and messages. Our friendship throughout the years until his death, was based on mutual trust and respect. As one brought up in the tradition of Igbo custom, Zik was my elder in age and indeed in everything else. Igbo society believes that although no condition is permanent, still no human society can achieve absolute equality for its citizens as there are distinctions of age, sex and wealth. Yet the dignity of every man was absolute. For instance, I am self-assertive as an Igbo, and Zik respected and valued it; as an Igbo also, I am not subservient, nor do I pay unquestionable obedience to everything Zik said. Zik admired and respected that also.

Zik had great faith in the immense ability of the peasantry to understand, and believed that they were just waiting to be enlightened. ..The editorials in the newspapers, especially those of the West African Pilot, were complemented by the humour, intelligence and acerbic satires of the various columnists. Among the best known columns were "Inside Stuff," written by Zik himself; "As I see it" by O.A Alakija; "A New Education for a New Africa" by Professor Eyo Ita; among others. The writers were all nationalists, and their essays were not only nationalistic but also educational. They showed black Africans and Nigerians the light. Many became prodigious readers, enabling them to acquire the dramatic force of conviction that propelled them to dare. Those columns became a form of literature for every school boy and girl, every worker, every one who could read and write. Certainly there began in Nigeria and all black Africa , a period of enlightenment, and the flowering of a new set of ideas about colonial rule and freedom from it.

As an instrument of propagating nationalism, equality of mankind and self-pride, their anti-colonial and nationalistic effect on the generation, our generation, and the era between 1937 and 1960 was unparalleled. No other previous or contemporary anti-colonial newspaper in Nigeria or elsewhere in black Africa had produced anything comparable in their influence towards a national spirit and towards Nigerian oneness.

In attacking imperialism and educating Nigerians, Zik’s writings were designed to appeal to every class - the common people, the youth, the intellectual, the rural as well as the city workers, and in a language which suited their emotion and which they understood. … He was a marvelous mob orator especially when he spoke concerned with the genuine hatred of imperialism and racial discrimination. His speeches always overwhelmed his audience, always moved them to immense enthusiasm, to a magnificent understanding of the evils of imperialism…

It is true that Zik’s age also had other politicians who emerged to join with him in the fight for independence, men no less sincere and probably no less devoted. But no one so vigorously, so single handedly or so successfully tried, as he did, in making every word and every act of his life a means towards a single objective, freedom from Britain as a SINGLE UNIFIED NIGERIAN NATION. As James Coleman testified, "During the fifteen year period (1939-1945) Nnamdi Azikiwe was undoubtedly the most celebrated nationalist leader on the West Coast of Africa, if not, in all tropical Africa", and that he was "the most single precipitator of the Nigerian awakening."

Certainly in 1930s and 1950s, Zik was the sole national leader, the sole nationalist inspirer, the sole intellectual, moral and political dictator in Nigeria against imperialism. He created an irresistible nationalist movement willing to overthrow colonial rule by peaceful means. He was an indomitable Moses preparing to lead his people out of Egypt . And he did. The emergence of Zik and his newspapers gave a new eloquence and ardor, a richer, more meaningful and emotionally charged anti-colonial message which profoundly effected more black Africans and Nigerians than ever before. No other black African or Nigerian before him or after, could claim to have aroused so many people across all the tribes, with direct and powerful nationalist political influence, as he did. Certainly, he exercised an intellectual and nationalist influence over many black Africans and Nigerians the strength of which was unique. He was the child of Africa and Nigeria and of Africa and Nigeria ‘s twentieth century prophetically calling for the end of colonialism and without violence. The verdict of history will record that this man Zik, had he done nothing else, that alone would have been sufficient to have assured him a lasting fame.

In conclusion, what Ikejiani said in closing the Foreword in the tribute to his friend, could very well he said of him by many who came to know him closely: He was indeed a great man. His life all reminds us about Longfellow’s Psalm of Life: Lives of great men all remind us; We can make our lives sublime, and in departing leave behind us foot prints in the sands of time."

Sunday, August 26, 2007

Ikejiani: Remembering His Tribute To Zik

Ikejiani: Remembering his tribute to Zik

DAILY CHAMPION LAGOS

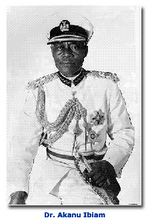

Okechukwu Ikejiani. Image via Ekwenche

News of the passing of one of the titans of modern Nigeria, Okechukwu Ikejiani, MD brought back memories of our first meeting over 12 years ago. That had been at the Lincoln University in Pennsylvania , as preparation for the return of the Great Zik, then almost 90 years old, to his alma mater, got under way. The late Vice Chancellor Prof. Chimere Ikoku called me from Enugu to know if I knew who Ikejiani was and whether I could reach him to start getting ready because for sure, Zik was coming, and after the US, he would be visiting with him in Nova Scotia.

That had been late in February or so. The Owelle, frankly, was far more concerned with seeing his two youngest sons graduate from Lincoln But word got out and the rest, as they say, was destined to become but history. As he had known all his life since his thirties, he was always one to attract more than a passing attention. Once Dr. Niara Sudarkasa, the president, secured commitment that the old legend was willing to travel, she could not believe the signals that went all over the world, commencing a series of activities that would occupy the small but historic campus for three long years. I know, because on recommendation as a past Nsukka alumnus and current university teacher with media and literary interests, I could be of help.

Indeed it was quite something to see the stirrings coming in from all quarters â€" the American government, Black American sororities who hadn’t seen ‘brother Zeek’ in ages, the Abacha government that was seeking its own legitimacy in the wake of its draconian hangman policies (having executed Ken Saro-Wiwa, chased 1993 election winner Moshood K.O. Abiola into exile, imprisoned Olusegun Obasanjo, clamped down on Shehu Yar’Adua and set up a murderous task force under one Major Mustafa);. There were the jostling Nigerian groups of all persuasions; the US media getting wind that one of the last of the great pan-Africanists was still alive and headed across the Atlantic , began making frantic inquiries. From the academic world came strong interests from US, British and Canadian scholars usually grouped around the African Studies Association. Same with Nigerian academics all over North America .

Trust Nigerian politicians and heavyweights anyone who could find a way to glimpse what was afoot, made an effort to what was really a small private visit with a reception being planned. Vice President Alex Ekwueme, Vice Chancellor Chimere Ikoku, Chief Sunny Odogwu, Princess Alakijia, Ambassador M. Kazaure, Chief Opral Shobowale Benson, Ambassador Ibrahim Gambari, Ambassador George Obiozor, by the scores they arrived. Even Chief MKO Abiola, then in exile from Abacha’s clutches, showed up unannounced and I was dispatched to interrogate his intentions along with Zik’s private secretary Okolo. Leading scholars like Ali Mazrui, Chinua Achebe, Michael Echeruo, Emmanuel Obiechina, leading American academics such as Harvard’s Martin Kilson, Richard Sklar of UCLA and many others

Crowds galore, the conference of reminiscences that I co-chaired (more like emceed really) with Sudarkasa, was a raucous one with the hall being rent with chants of Zeek! Zeeek!

In all that convivial atmosphere of reunion, pan-Africanist reminiscences and the high-politics of US-Nigeria relations then at their lowest ebbs, one man stood out above everyone else as the Owelle’s personal associate, friend and boon companion the dapper elderly gentleman in thick glasses, a nice suit with a cut that bespoke 1950s elegance, and a quiet sense of confidence that this was a historic enough of an occasion to warrant a break from his solitude. They pointed out the legendary Dr. Okechukwu Ikejiani to me, one of those stand-outs from the 1959s and 1960s whose name I believe I first heard from Ikenna Nzimiro as we once browsed the books in his extensive library of which he had been so proud. It was only later that I came to know that the future minister, Prof. Miriam Ikejiani-Clark (Miriam Okadigbo in those days and wife of the flamboyant former adviser to President Shagari, Dr. Chuba Okadigbo), was his daughter.

Zik would be back again the next year to see his last boy get his laurels before heading to law school, at a quieter gathering, but Ikejiani would also come along with his friend, as would Ekpechi. That was in 1995. Zik died in 1996. In 1997, Lincoln would again host the world to a final assessment of the author of ˜Renascent African, the man whom everyone from J.S. Tarka would call the single most important man in Nigerian history and T.O.S. Benson would in his recent biography, recall as the tallest tree in the Nigerian political jungle. And that would witness an even bigger parade of dignitaries from far and wide Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Shehu Shagari of Nigeria, former Petroleum minister Shettima Ali Munguno, Prof. Adebayo Adedeji, the Oni of Ife, Benson himself, the Emir of Kano Ado Bayero, ambassadors from East and West Africa, scores of academics, politicians, African American pan-Africanists, some of whom had been to the famed Manchester pan-African congress of 1945 and were very much aware of Zik’s grand influence.

Ikejiani was not able to attend that final conference, being sick already 80 at the time, the frequent flyer lifestyle was one he needed to put in check. But he had been with us in 1996 when I brought him over to be keynote speaker at the memorial the Nigerian community held for Zik at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine at Columbia University . Then he had spent the weekend with crowds cramming my sitting room as he reflected on an age that was already becoming mythical a mere half century later.

It was in that spirit that I had convinced him to write the Foreword to my book on Zik, The Man Called Zik of New Africa: A Portrait of Nigeria’s Pan-Africanist Statesman (the title was modified for the second edition). I recall the foregoing piece of history because of its relationship to Ikejiani who should be remembered, not just for his many other sterling attainments as medical director at Glace Bay Hospital, Canada; as a former Pro-Chancellor, University of Ibadan, as author, Education in Nigeria, as chairman of the Nigerian railways when it actually worked, and as a humanist whose training in medicine belied a larger intellectual capability. I recall also a man of culture, dignity and sense of history. A man of character, too. His account of Zik’s generosity in opening the doors to higher education and sponsoring as many as he could for the trans-Atlantic quest for the Golden Fleece as they called it in those days, speaks to a side of the Owelle that few biographers have dwelt on. It also shows Ikejiani as a man able to appreciate a good turn in life and speak to its lasting value. Here is an excerpt from the Foreword.

The first time I saw the late Right Honorable Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe was at Onitsha on November 17, 1934 at the Native Court hall, at a reception given in his honor by the community. I was just completing my first year of high school at the Dennis Memorial Grammar School , Onitsha . I went along with some students to the lecture. The hall was full and packed and we were not able to gain entrance to the hall. We listened to his lecture standing outside the building. The late Rt. Hon. Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe spoke of what a new African could equally do. He told us that Nigeria must be free from colonialism to achieve such equality. For the first time my life, I began to understand what colonialism meant and to question it. I discarded the idea previously held by us that we were inferior to white people.

Between 1935 and 1936, The African Morning Post, the newspaper which Azikiwe published and edited in Accra , Gold Coast - now known as Ghana - reached us on a regular basis. We read and crammed most of its editorials and leading columns, and for the first time, we began to believe that this man Zik was God-sent to Africa .

The first time I met Zik in person was not until 1937, when he had returned from Accra , Ghana , to Onitsha . I was a third year student in secondary school. On a Sunday morning, as was usual practice, as we marched in groups to Christ Church located near the River Niger water-side, four of us left our group and made our way to the house where Zik was staying along the New Market Road , almost opposite Venn Road . When we said to the people there that we wanted to see Zik, a tall man standing in front of the house said to us, "I am Zik. What can I do for you?" I replied on behalf of all of us with great trepidation, "Sir, we want to go to America ." He replied and told us that if our parents or guardians could provide fifty pounds a year each for us, he could help us to go to America . We all ran away back to the dormitory informing those who would listen that Zik would help us go to America .

I met Zik again in Lagos on December 1938. I was one of the eight young men who met him at his West Africa Pilot office, Market Street , Lagos , when he again asked us, "What can I do for you?" We replied that he told us that he would help us to go to America if our parents or guardians could afford to support us with fifty pounds a year. "Do you have the fifty pounds and the transportation money?" he asked us, and we replied in unison, "Yes, Sir." He counted the money we brought, which was in shillings and pennies.

My money contained one pound and ten shillings counterfeit! I was distraught and began to cry. He comforted me and replaced the counterfeit money. He proceeded to make all the arrangements for all of us. True enough, came December 1938, the eight of us left Apapa and sailed for the United States of America to embark on further studies. It was a very historic event in Nigeria with throngs of people coming to see us off at the wharf.

Zik assisted dozens of Africans to go on to the United States for university education. In assisting and helping us and those that had gone before us, like late Kwame Nkrumah just about a year after he has returned to Nigeria from Ghana was a great way of showing the light. K.O. Mbadiwe, A.A. Nwafor Orizu, and others like Jones-Quartey, Karimu Disu, Kalu Ezera, etc., all travelled under his aegis.

I met Zik again in August 1948 when I returned from the United States of America and Canada , after many years of sojourn there. It happened that my wife was a white lady, nee Marjorie Carter. Rumor had reached the Igbo State Union that I was returning with wife. The Igbo Union executives met with Zik and informed him about what they had heard. They said that because of that, they would not give me the reception they were planning for me. He asked them whether I wrote to them that I was returning and they should accord me a reception. They said no. He thereupon told that he did not think that I would be expecting their reception. Zik added that he was going to Apapa to meet me and my wife and that we were going to be his host as long as we stayed in Lagos . That shocked them and completely cured them of the race hatred which they harbored. That notwithstanding, I was given receptions galore on our return wherever we went throughout Igboland.

From the moment of my return in 1948, a deep and abiding friendship developed between Zik and I. This friendship grew by leaps and bounds over the years - and I came to learn a lot about him. From that incident in 1948, I realized that this man called Zik was not prejudiced against white people. As an Igbo, like him, raised in the same environment that influenced his basic character, I communicated with him in the same language and understood the riddles and real meanings behind his remarks, statements and messages. Our friendship throughout the years until his death, was based on mutual trust and respect. As one brought up in the tradition of Igbo custom, Zik was my elder in age and indeed in everything else. Igbo society believes that although no condition is permanent, still no human society can achieve absolute equality for its citizens as there are distinctions of age, sex and wealth. Yet the dignity of every man was absolute. For instance, I am self-assertive as an Igbo, and Zik respected and valued it; as an Igbo also, I am not subservient, nor do I pay unquestionable obedience to everything Zik said. Zik admired and respected that also.

Zik had great faith in the immense ability of the peasantry to understand, and believed that they were just waiting to be enlightened. ..The editorials in the newspapers, especially those of the West African Pilot, were complemented by the humor, intelligence and acerbic satires of the various columnists. Among the best known columns were "Inside Stuff," written by Zik himself; "As I see it" by O.A Alakija; "A New Education for a New Africa" by Professor Eyo Ita; among others. The writers were all nationalists, and their essays were not only nationalistic but also educational. They showed black Africans and Nigerians the light. Many became prodigious readers, enabling them to acquire the dramatic force of conviction that propelled them to dare. Those columns became a form of literature for every school boy and girl, every worker, every one who could read and write. Certainly there began in Nigeria and all black Africa , a period of enlightenment, and the flowering of a new set of ideas about colonial rule and freedom from it.

As an instrument of propagating nationalism, equality of mankind and self-pride, their anti-colonial and nationalistic effect on the generation, our generation, and the era between 1937 and 1960 was unparalleled. No other previous or contemporary anti-colonial newspaper in Nigeria or elsewhere in black Africa had produced anything comparable in their influence towards a national spirit and towards Nigerian oneness.

DAILY CHAMPION LAGOS

Okechukwu Ikejiani. Image via Ekwenche

News of the passing of one of the titans of modern Nigeria, Okechukwu Ikejiani, MD brought back memories of our first meeting over 12 years ago. That had been at the Lincoln University in Pennsylvania , as preparation for the return of the Great Zik, then almost 90 years old, to his alma mater, got under way. The late Vice Chancellor Prof. Chimere Ikoku called me from Enugu to know if I knew who Ikejiani was and whether I could reach him to start getting ready because for sure, Zik was coming, and after the US, he would be visiting with him in Nova Scotia.

That had been late in February or so. The Owelle, frankly, was far more concerned with seeing his two youngest sons graduate from Lincoln But word got out and the rest, as they say, was destined to become but history. As he had known all his life since his thirties, he was always one to attract more than a passing attention. Once Dr. Niara Sudarkasa, the president, secured commitment that the old legend was willing to travel, she could not believe the signals that went all over the world, commencing a series of activities that would occupy the small but historic campus for three long years. I know, because on recommendation as a past Nsukka alumnus and current university teacher with media and literary interests, I could be of help.

Indeed it was quite something to see the stirrings coming in from all quarters â€" the American government, Black American sororities who hadn’t seen ‘brother Zeek’ in ages, the Abacha government that was seeking its own legitimacy in the wake of its draconian hangman policies (having executed Ken Saro-Wiwa, chased 1993 election winner Moshood K.O. Abiola into exile, imprisoned Olusegun Obasanjo, clamped down on Shehu Yar’Adua and set up a murderous task force under one Major Mustafa);. There were the jostling Nigerian groups of all persuasions; the US media getting wind that one of the last of the great pan-Africanists was still alive and headed across the Atlantic , began making frantic inquiries. From the academic world came strong interests from US, British and Canadian scholars usually grouped around the African Studies Association. Same with Nigerian academics all over North America .

Trust Nigerian politicians and heavyweights anyone who could find a way to glimpse what was afoot, made an effort to what was really a small private visit with a reception being planned. Vice President Alex Ekwueme, Vice Chancellor Chimere Ikoku, Chief Sunny Odogwu, Princess Alakijia, Ambassador M. Kazaure, Chief Opral Shobowale Benson, Ambassador Ibrahim Gambari, Ambassador George Obiozor, by the scores they arrived. Even Chief MKO Abiola, then in exile from Abacha’s clutches, showed up unannounced and I was dispatched to interrogate his intentions along with Zik’s private secretary Okolo. Leading scholars like Ali Mazrui, Chinua Achebe, Michael Echeruo, Emmanuel Obiechina, leading American academics such as Harvard’s Martin Kilson, Richard Sklar of UCLA and many others

Crowds galore, the conference of reminiscences that I co-chaired (more like emceed really) with Sudarkasa, was a raucous one with the hall being rent with chants of Zeek! Zeeek!

In all that convivial atmosphere of reunion, pan-Africanist reminiscences and the high-politics of US-Nigeria relations then at their lowest ebbs, one man stood out above everyone else as the Owelle’s personal associate, friend and boon companion the dapper elderly gentleman in thick glasses, a nice suit with a cut that bespoke 1950s elegance, and a quiet sense of confidence that this was a historic enough of an occasion to warrant a break from his solitude. They pointed out the legendary Dr. Okechukwu Ikejiani to me, one of those stand-outs from the 1959s and 1960s whose name I believe I first heard from Ikenna Nzimiro as we once browsed the books in his extensive library of which he had been so proud. It was only later that I came to know that the future minister, Prof. Miriam Ikejiani-Clark (Miriam Okadigbo in those days and wife of the flamboyant former adviser to President Shagari, Dr. Chuba Okadigbo), was his daughter.

Zik would be back again the next year to see his last boy get his laurels before heading to law school, at a quieter gathering, but Ikejiani would also come along with his friend, as would Ekpechi. That was in 1995. Zik died in 1996. In 1997, Lincoln would again host the world to a final assessment of the author of ˜Renascent African, the man whom everyone from J.S. Tarka would call the single most important man in Nigerian history and T.O.S. Benson would in his recent biography, recall as the tallest tree in the Nigerian political jungle. And that would witness an even bigger parade of dignitaries from far and wide Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Shehu Shagari of Nigeria, former Petroleum minister Shettima Ali Munguno, Prof. Adebayo Adedeji, the Oni of Ife, Benson himself, the Emir of Kano Ado Bayero, ambassadors from East and West Africa, scores of academics, politicians, African American pan-Africanists, some of whom had been to the famed Manchester pan-African congress of 1945 and were very much aware of Zik’s grand influence.

Ikejiani was not able to attend that final conference, being sick already 80 at the time, the frequent flyer lifestyle was one he needed to put in check. But he had been with us in 1996 when I brought him over to be keynote speaker at the memorial the Nigerian community held for Zik at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine at Columbia University . Then he had spent the weekend with crowds cramming my sitting room as he reflected on an age that was already becoming mythical a mere half century later.

It was in that spirit that I had convinced him to write the Foreword to my book on Zik, The Man Called Zik of New Africa: A Portrait of Nigeria’s Pan-Africanist Statesman (the title was modified for the second edition). I recall the foregoing piece of history because of its relationship to Ikejiani who should be remembered, not just for his many other sterling attainments as medical director at Glace Bay Hospital, Canada; as a former Pro-Chancellor, University of Ibadan, as author, Education in Nigeria, as chairman of the Nigerian railways when it actually worked, and as a humanist whose training in medicine belied a larger intellectual capability. I recall also a man of culture, dignity and sense of history. A man of character, too. His account of Zik’s generosity in opening the doors to higher education and sponsoring as many as he could for the trans-Atlantic quest for the Golden Fleece as they called it in those days, speaks to a side of the Owelle that few biographers have dwelt on. It also shows Ikejiani as a man able to appreciate a good turn in life and speak to its lasting value. Here is an excerpt from the Foreword.

The first time I saw the late Right Honorable Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe was at Onitsha on November 17, 1934 at the Native Court hall, at a reception given in his honor by the community. I was just completing my first year of high school at the Dennis Memorial Grammar School , Onitsha . I went along with some students to the lecture. The hall was full and packed and we were not able to gain entrance to the hall. We listened to his lecture standing outside the building. The late Rt. Hon. Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe spoke of what a new African could equally do. He told us that Nigeria must be free from colonialism to achieve such equality. For the first time my life, I began to understand what colonialism meant and to question it. I discarded the idea previously held by us that we were inferior to white people.

Between 1935 and 1936, The African Morning Post, the newspaper which Azikiwe published and edited in Accra , Gold Coast - now known as Ghana - reached us on a regular basis. We read and crammed most of its editorials and leading columns, and for the first time, we began to believe that this man Zik was God-sent to Africa .