By Chika Okeke-Agulu, Huffington Post

On Wednesday, December 4, the Press Office of the Venice Biennale

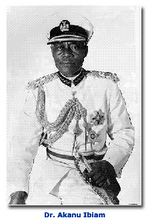

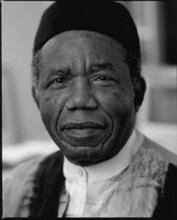

announced the appointment of the Nigerian-born curator and scholar

Okwui Enwezor as the director of the 56th Venice Biennale scheduled for

2015. In this interview, Enwezor discusses his career and the

significance of his latest curatorial project.

Chika Okeke-Agulu: At the opening of Documenta11 in

2002, I remember saying to you that the next big challenge would be

Venice. I said it as a kind of joke, but not because I did not think you

could do it. Rather I was aware that only one other person--the

legendary Harald Szeeman--had

curated both Documenta and Venice. In any case, since Documenta you

have organized Gwangju and Seville Biennales, as well as La Triennale,

Paris, and now, Venice. I cannot imagine what it feels to join Szeeman

in this curatorial pantheon?

Okwui Enwezor: Thanks Chika. That's extremely kind

of you to make a comparison with me and Szeeman. I know this question

will inevitably come up, and I want to be as clear as possible, I belong

to no pantheon. There really isn't a comparison; Szeeman is entirely

in a league by himself. In the abundance of his ideas, the almost carnal

fervor for artists, artworks, and objects of all kinds, along with his

bold, original curatorial experiments, he paved the path to the thinking

that curatorial practice need not be too studied, formalist or

dogmatic.

The fact that we are the only two curators to have helmed both

Documenta and Venice Biennale is a historical happenstance; but one

who's significance is still settling in. It is of course, a great honor

to be entrusted with the task of organizing an exhibition of this

magnitude and international acclaim. Nevertheless, it is not lost on me

that there is some kind of meaning in the symbolism to which you drew

attention. Exactly 15 years ago, I got handed the reins of organizing

Documenta. I was 35 at the time, I had limited track record, no major

institution, patron, mentor, behind me, yet somehow that amazing jury

that selected me saw beyond those deficits and focused, I hope, on the

force of my ideas, and perhaps even a little wager on the symbolism of

my being the first non-European, etc. My sense of it was that the jury

wanted a choice that could be disruptive of the old paradigm but still

not abandon the almost mythic ideal of this Mount Olympus of

exhibitions.

I came to Documenta as I said with little track record, but with an

abundance of confidence. Now at fifty, I come to Venice with a different

set of lenses and experience. As you mentioned I have now organized

quite a number of biennials. It's time to get to work.

C. O.: Documenta11 was one of the few exhibitions

that have been called game changers in the history of curating. And

this, I believe had to do with your introduction of the multiple

platforms scattered across the globe, as the constitutive sites of an

event that until then only took place in Kassel. What are your

preliminary thoughts about how you might approach Venice, given its

history and structure?

O. E.: It's too early to say what shape the 56th

Venice Biennale will take. Of course, I have some preliminary ideas, but

those will be worked out in due course. The one virtue of Documenta is

the time allowed to organize it, which made possible the platforms. But

you must remember that the platform idea, which was fundamentally about

the deterritorialization of Documenta, was not initially endorsed by

certain landlocked critics, but once it took off its implications about

going beyond business as usual became abundantly clear. I drew

enormously from the Igbo saying: "Ada akwu ofuebe ekili nmanwu." The

mobility of the platforms across major cities and some not so major ones

was premised on this principle. To see the artworld properly as it

should be, to engage in meaningful debate the curator must risk the

sense of inquisitive wanderlust. However, Venice is an Island, but also a

legendary maritime trading city that historically looked out to the

rest of the world. The limited time permitted to organize the biennale

produces a certain sense of temporal density. I am certainly thinking

about how to surmount this conundrum.

C. O.: Looking at the trajectory of your career,

from the early 1990s when, with a few friends and colleagues working in

the margins of the contemporary art world, you founded Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art,

to becoming a leading academic, administrator and curator in the field

of contemporary art, does it sometimes feel like an improbable story?

O. E.: All stories are improbable. Nothing is

preordained. No one is born with a straight arrow in his quiver. It's a

combination of relentless work and good fortune. Without this

improbability there is no risk, no adventure, no discovery. I am an

autodidact which was the basis of my ceaseless and restless appetite for

ideas. I learned enormously about art, not in an art history seminar (I

don't even recall actually taking one) but by seeing enormous number of

exhibitions, being in the presence of art and artists every week,

everywhere. I still do, and I maintain the exercise of seeing, reading,

thinking, and writing.

I arrived in New York in late summer of 1982, at a pivotal point in

the development of contemporary art, fashion, performance, music, etc.

in the city. I was a beneficiary of the perfect storm of creative

upheaval: art, postmodern and postcolonial theory, identity politics:

race, sexuality, gender, queer and feminist activism, and the AIDS

pandemic further refreshed my perspective on difference and politicized

my response to injustice. This was the context that opened me up to

complexity and to thought me to be courageous and fearless.

Also, Coming from Nigeria I felt I owed no one an explanation for my

existence, nor did I harbor any sign of paralyzing inferiority complex.

What was apparent was that most Americans I knew and met were actually

not worldly at all, but utter provincials in a very affluent but unjust

society. And when this became clear I saw no reason why I could not have

an opinion or a point of view. I was not about to be respectful of

ignorance of Africa or prejudice against African culture. This gave me

some chutzpah.

I started learning about what was going on in downtown New York

across every cultural and literary sphere through publications like Village Voice,

Detail, Seven Days. I attended openings, went to readings, saw an

enormous number of exhibitions, in every imaginable context, from

apartments to Soho galleries, to alternative spaces to museums,

nightclubs such as Danceteria, Area, Pyramid Club, Peppermint Lounge, Palladium, Save the Robots, The World,

Roxy, Madam Rosa's, and later Nell's, Mars, you just name it. I was

educated as it were in situ. I can actually say that I was there.

At some point this intense experience as a young Nigerian who was

deeply interested in art and all types of the creative process ceases to

be a fluke. I don't believe in standing on the margins. You should also

know that what partly made Nka viable was that I did actually have a

deep knowledge of international contemporary art. I was not pretending.

When I started thinking of setting up Nka in 1991 when I was in my

twenties, I was intellectually ready and had a certain theoretical

grounding and immersion in art, visual culture, etc. I was already

collecting a bit of photography and some art. My first major acquisition

was the portrait of Jean-Michel Basquiat by James Van der Zee from Howard Greenberg Gallery

on Wooster Street. I would go to the Comme des Garçon boutique

downstairs to shop and up to the Greenberg Gallery to browse vintage

prints by Cartier Bresson, Kertescz, Weston, Moholy Nagy, Baron de

Meyer. So with Nka It wasn't as if I did not know what I was talking

about. The only reason it also worked was because I had the language and

it was fresh and people were open to giving it audience. That it led to

where I am standing today is both surprising and thrilling. But we are

nearly thirty years into this story. The novelty of endless looking back

is wearing off. Obama's campaign slogan in the last election against

the hapless Mitt Romney had it exactly right: Forward.

C. O.: Are you going to retire from curating biennales after Venice?

O. E.: I am not the retiring type.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment